Welcome to your deepest fears and nightmares…

Not really, this is just Blog 101

For the few people who did not read it, Blog 100 comprised a quiz based on the previous 99 Blogs. This Blog gives you the answers and the results (see bottom of page). If you want to do the quiz, without cheating, go back to number 100.

The Answers

1: How long was the biggest nematode worm ever found?

Answer: 8.5m in the pancreas of a sperm whale.

2: Which video on this blog has had more than 86,000 views?

(Quite astonishing given the subject matter)

Answer: How to plot custom error bars in Excel. I made this for my 20-odd Open University Students but it proved popular with people (like me) all over the world who found the Excel help system incomprehensible) .

3: The rocks of the Dale Peninsula are red, why?

Answer: The rock is called old red sandstone. It is stained red because it contains an iron compound, which is fully oxidized (like red rust). The sandstone consists of a matrix of this compound (iron (III) oxide) holding together harder particles of quartz.

4: Where did the slate flagstones in Dale Fort come from?

Answer: They probably came from Rosebush (or maybe Abereiddy) in North Pembrokeshire. They were formed around 500 million years ago, when fine sedimentary shales were metamorphosed into slate as a result of heat produced by earth movements and the intrusion of molten material from below.

5: What is the big brown seaweed from Japan that’s colonising European shores?

Answer: Sargassum muticum (used to be called Japweed, these days an unacceptably racist term, so has been renamed wireweed (which is of course wireist). Remarkably, humans can find ways to be offensive about anything, even seaweed names.

6: What’s a potboiler?

Answer: These are stones, cracked or shattered by rapid cooling as a result of being heated in a fire and dropped into cold water in cooking vessels, thus heating the water and cooking the food. Hot stones may have also been used to make a type of a sauna bath.

7: Who pioneered the futon on the Dale Peninsula?

Answer: Me. Between 1985 and 1988 when I was privileged to live at Dale Fort, I developed a sleeping arrangement then revolutionary on The Dale Peninsula. I spent each night on the floor, on a thin roll-upable mattress that I could pack away into a cupboard every morning. Pioneering the futon meant I could maximise the floor area of my very small room during the few conscious moments I spent there when not teaching. A secondary benefit was that I developed a close acquaintance with the thousands of silverfish who shared the accommodation.

8: What do book lice eat?

Answer: Most books are made from wood which is not an easy thing to subsist on. Wood-eating animals like termites can only digest it with the aid of the complex community of micro-organisms that dwell in their guts (baby termites inoculate themselves with these organisms by licking their mother’s bottoms and starve if they don’t). Booklice can’t eat books directly but chomp instead upon the moulds and fungi that can. Two stiff rods support the head while the biting jaws chew up the food. It could be argued that booklice are a force for book-conservation because they remove paper and gum digesting fungi. In the long run, it’s probably better to get rid of both. An easy way to do this is to heat and desiccate them (a hair dryer will do the job). You should think carefully before applying this treatment to your First Folio Edition Shakespeare.

9: Why does ice float on water?

Answer: Water molecules have a positive end (the hydrogen atoms) and a negative end (the oxygen atom). As they cool the negative bits glue on to the positive bits and make a crystal lattice, which is less dense that the liquid water they originated from. This (I think?) makes water unique and life as we know it possible.

10: How many bait digger’s holes were found on The Gann Site of Special Scientific Interest when Dale Fort mapped them?

Answer: 26,615. There’s now a Natural Resources Wales voluntary code in place to try to manage the site. The main problem being that there’s nobody to do the enforcing, so what’s the point? A lot of conservation legislation seems to follow this approach. Where are the worm police when you need them?

11: What is the grazing organ of a limpet called?

Answer: A radula. Actually a formidable bit of kit as you’ll know if you looked at Blog 11. The radula teeth are the hardest substance yet found in living creatures.

12: Upon what did Saint Bridget hang her cloak to dry?

Answer: A sunbeam, thus proving her saintliness.

13: What did Saint David preach against at The Synod of Brefi in 545 AD?

Answer: The Pelagian heresy. Pelagius said that original sin was nonsense and that salvation could be attained by individuals, without the need for the church. The church was miffed about this.

14: What do the terms “trap happy” and “trap shy” mean?

Answer: To catch and mark a small mammal you use a baited trap with nesting material in it (a Longworth trap, look it up). Mammals are good at learning and some quickly realise that getting trapped means free bed and breakfast, no predators and the enticing prospect of escaping into the huge beard of the bloke who opens the trap and there building a cosy nest. Such individuals are called trap-happy because they actively seek out traps. The opposite extreme is where individuals find the prospect of being trapped and meeting the ecologist with his vile smelly beard appalling. These individuals actively avoid the traps and are known as trap-shy animals. If you have individuals of either persuasion (or both) in the population then your estimate is unlikely to be correct.

15: Why are female mosquitoes far scarier than than the chaps?

Answer: Males eat fruit and decomposing vegetation. Females suck your blood and might give you malaria or dengue fever. The females need extra protein to produce their eggs.

16: What is orpiment?

Answer: An arsenic sulphide compound imported to mediaeval Wales from either (present day) Italy or Kurdistan. Orpiment was the only means of producing a clear yellow colour in hand-written manuscripts. It was extremely expensive.

17: How big is a mouses bladder?

Answer: Very small. Mice leave a trail of wee everywhere they go.

18: What does the old Norse name “Grassholm” mean in English?

Answer: Green Island.

19: What is pogonophobia?

Answer: Fear of beards.

20: What is the oldest frequently spoken language in Europe?

Answer: Welsh.

21: What is the standard deviation of the mean?

Answer: They (the mean) think that their attitude will bring them happiness and satisfaction. It won’t. It’s also a measure of how far a set of data varies either side of its arithmetic mean.

22: What was The Giant Bat of St. Bride?

Answer: A bin liner, wrapped around a chimney pot.

23: What is a frequency distribution?

Answer: Do you really want to know? Maybe you should get out more? It’s a kind of graph, that can be very useful in showing the general shape of a set of data. See Blog Number 23.

24: What is the name of the pub In Dale?

Answer: The Griffin, watch the video.

25: Who hated a barnacle as no man ever did before?

Answer: Charles Darwin.

26: What is the oldest structure designed for ordnance in Milford Haven?

Answer: East Blockhouse c1579.

27: What multicellular creatures can survive in outer space without spacesuits?

Answer: Tardigrades.

28: What do house dust mites eat?

Answer: Human skin.

A contented flock of house dust mites graze across your underwear

29: What creatures terrified the protagonist in Edgar Allen Poe’s story The Tell Tale Heart?

Answer: Death Watch Beetles.

30: In 1930, why did a policeman stop the traffic on Tower Bridge?

Answer: To allow a huge house spider to cross the road safely.

31: What was The Black Legion?

Answer: An Irish-American mercenary named Tate had been put in charge of a force of around 1500 Frenchmen, mostly from French military prisons. They were dressed in uniforms captured from French Royalists, originally red but now dyed almost black, they were known as Le Legion Noire (The Black Legion). They made a successful landing in 1797, not far from Milford Haven, at Carreg Wastag near Fishguard. It was the last invasion of mainland Britain.

32: What colour is phycoerythrin?

Answer: Red, it’s found in red seaweeds.

33: When did the oil tanker Sea Empress first crash into the rocks near St Anne’s Head?

Answer: 15th February 1996.

Years ago, I was giving a talk about the Sea Empress oil spill to a group of students from a very posh English public school. One of the students said, “my dad took that picture”. This photograph was taken illegally since the government had banned private aeroplanes from flying over the scene. I believe he got fined a few thousand pounds. However, the picture was syndicated worldwide and he made a small fortune, thus enabling him to fund his daughter’s very expensive education. I hope if he sees this, he will also refrain from suing me because this picture can be seen all over the place and I doubt if everyone’s paying.

34: What is Melarhaphe neritoides?

Answer: A small snail that lives in the upper shore and splash zone.

Small winkles, big picture

35: Which Emperor of France was a special constable in London?

Answer: Charles Louis Napoleon. He escaped imprisonment in France in 1846, fled to London where he joined the special constabulary and helped his chums beat up The Chartists.

Charles Louis and friends attack people who would like to vote.

36: What is a null hypothesis?

Answer: An hypothesis of no difference, invented for the sole purpose of bamboozling non statisticians.

37: What animal paddled into the middle of the pond on Skokholm at the sound of the supply vessel?

Answer: The donkey that pulled the cart (it could hear the boat before the humans had spotted it and knew it would get bribed with carrots to entice it from the water).

38: Who is the cocker spaniel?

Answer: The much missed Meggie.

39: Where is the source of the Afon Synfynwy?

Answer: In The Preseli Mountains.

40: What does Aberdaugleddau mean in English?

Answer: Mouth of the two Cleddaus.

41: What is the smallest city in the UK?

Answer: St. Davids.

42: Where in Pembrokeshire can you discover the truth about longshore drift?

Answer: Newgale (at least as far as this blog is concerned).

43: How many musketry loops are there in The Defensible Barracks at Pembroke Dock?

Answer: 712. They needed this many because of the slow rate of fire of muzzle loading firearms.

44: Which champion of marine conservation informed me that: “Limpets are my f***ing business Steve…”?

Answer: The Great Bill Ballantine. Very posh accent plus foul language equals very funny (in my book anyway).

45: What does a baby termite have to do before it can digest its food (wood)?

Answer: Lick its mother’s anus (so it can inoculate itself with the necessary bacteria to enable wood digestion).

46: What marine mollusc has up to a 100 blue eyes and is jet propelled?

Answer: The scallop.

47: What is a murmuration?

Answer: A mass of starlings flying about in formation and looking astonishing.

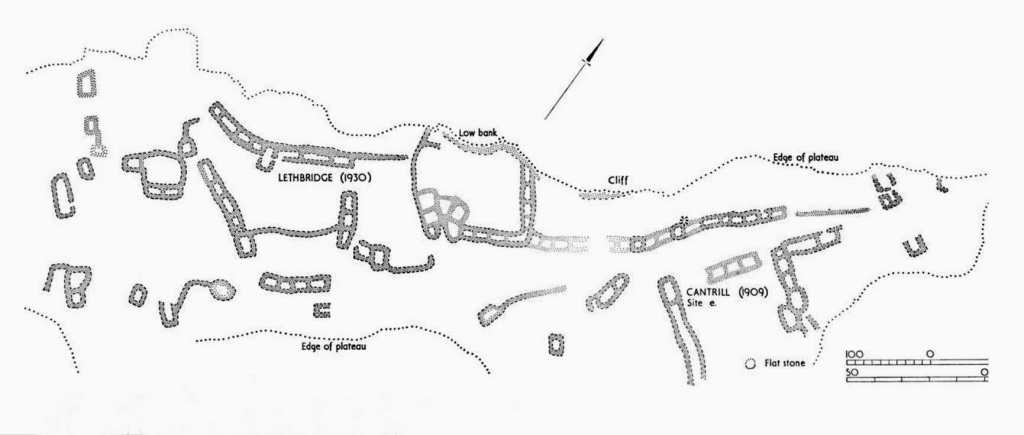

48: What was the carbon date obtained for the earliest known Dale Fort?

Answer: 790 BC.

49: What was Chain Home Low?

Answer: An early radar system providing early warning of approaching baddies (the Germans in this case).

50: Who was the military engineer most probably responsible for the construction of Dale Fort?

Answer: Lieutenant Colonel Victor RE.

51: Who is Juligan Inglesius?

Answer: The provider of the background music for this video. You may have guessed it was me in Latin mode, guitar footling (there have to be a few difficult questions, or everyone will win and I’ll have to provide 100 copies of Scattering Dreams).

52: Who was the earliest named victim of gingism in Pembrokeshire?

Answer: Simon. In 1188 Gerald of Wales mentioned a man called Elidyr de Stackpole, the owner of the Stackpole Estate. Elidyr founded the church and employed Simon de Gingo (he had red hair) to look after things. Simon made sure everyone (the workers included) was well fed and housed and spent a lot of Elidyr’s money. He didn’t live on the estate but seemed to vanish at night. He was instructed to economise but failed to do so. As a result, a member of the Elidyr family followed him one night and reported seeing him turn into a demon and consort with a bunch of other demons down by the mill pond. Simon’s mum confirmed that actually, she’d been ravished by the devil (disguised as her husband) and 9months later out came Simon.

53: What is an actinomorphic flower?

Answer: One that is radially symmetrical.

54: What is a stigma (in terms of parts of a flower)?

Answer: A sticky tip (ooh err missus…).

55: What is rifling?

Answer: Spirals cut inside a barrel to impart spin to a projectile.

56: Why would you not use ferrous metals in a powder magazine?

Answer: Ferrous metals spark easily and gun powder explodes when exposed to sparks.

57: What was La Gloire?

Answer: The first French iron clad, steam powered battle ship.

58: What Does RnkAvg stand for in Excel?

Answer: Rank Average zzzzzzz……..

59: What is an MCZ?

Answer: A Marine Conservation Zone.

60: Who drew the earliest known plan of the present Dale Fort?

Answer: Lieutenant Stanford (1866).

61: Who was Scalm?

Answer: The first named Icelandic Horse (12th century).

62: What is the largest predator on earth?

Answer: The sperm whale. The males can grow to 20m long and weigh 50 Tonnes. Mostly they eat giant and colossal squid from the deep oceans.

63: Why do rabbits do so well on Skomer and Skokholm?

Answer: No ground predators, lots of grass.

64: What sounded like the wail of a discontented elephant?

Answer: The Zalinski Pneumatic Dynamite Gun.

65: What % (by weight) water loss can Fucus serratus ( serrated wrack) tolerate?

Answer: About 40%.

66: What year did Noddy’s Hat get broken?

Answer: 2018.

67: What does Creigiau Preseli mean in English?

Answer: Elvis Rocks.

68: What was the name of Colonel Owen Evans’s dog?

Answer: Shot.

69: What was M. A. Bland known as?

Answer: MAB.

70: How much water loss (by weight) can Fucus vesiculosus (bladder wrack) tolerate?

Answer: About 70%.

71: What is an anaerobic organism?

Answer: One that lives in the absence of oxygen.

72: What is Ascophyllum nodosum?

Answer: A big brown seaweed, watch the video, it’s amazing (the seaweed probably not the video).

73: Who on the shore has flashing headlamps?

Answer: Flies of the family Dolichopodidae (usually called Dolichops flies).

74: What species of red seaweed can you buy on Swansea Market?

Answer: Porphyra known in Wales as laver, boiled for hours, fried and as delicious as you’d expect.

75: Where was the largest oil fire the world had ever seen until the first Gulf War took over this dubious honour?

Answer: The oil depot at Pembroke Dock (the biggest in the world), bombed by The Luftwaffe in August 1940.

77: What entered the sea via a blue silk parachute?

Answer: Magnetic mines, dropped by The Luftwaffe.

78: What does LCG stand for?

Answer: Landing Craft Guns.

79: How many military personnel were stationed in and around Dale during World War Two? (To the nearest thousand will do).

Answer: 4000.

80: Who invented the nun shrinking machine?

Answer: Mary-Kate Morrell. Well, her idea, my execution.

81: Who was the first warden of Dale Fort Field Centre?

Answer: John Barrett.

82: When was the first recorded field course at Dale Fort?

October 25th – 26th 1947. John Barrett gave members of The West Wales Field Society a tour of The Gann Estuary, mainly looking for Autumn migrant birds.

83: Who helped fire a volley of King Edwards potatoes at an Icelandic trawler during the first action in The First Cod War?

Answer: The second warden of Dale Fort, David Emerson, as Navigating Officer on a British Navy frigate. They were responding to a shower of cod’s heads catapulted from the trawler.

84: How much aggregate was needed for the main runways of Dale Airfield? (This one’s for Simon).

Answer: My calculation based on a little knowledge and a lot of internet comes to about 120,000 Tonnes.

85: How do Natural Resources Wales know if someone if breaking their code of practice for worm digging at The Gann SSSI?

Answer: They don’t unless somebody tells them. This is their email: icc@naturalresourceswales.gov.uk let them know.

86: What salt marsh plant is sometimes called “poor man’s asparagus”?

Answer: Salicornia (which means salty horn in Latin). A more appropriate name these days, given its use in posh restaurants might be “rich man’s novelty vegetable”.

87: Sea pink, thrift, Armeria maritima. Three names for the same plant. What languages does the generic name (Armeria) derive from?

Answer: Welsh, ar mor = by the sea, Latin, maritimus = of the sea. Only a suggestion but possibly the only flowering plant with a name partially derived from Welsh.

88: Which salt marsh plant tastes of coriander (apparently) and is best avoided if very hungry?

Answer: Sea arrow grass (Triglochin maritima). There are morons on the internet that will tell you that this is an edible species. It contains cyanide when mature, so do not let it anywhere near your mouth (or indeed any orifice) is my advice.

89: Which coasts are the native habitats of Sargassum thunbergii?

Answer: The coasts of China, Japan and Korea.

90: What are the main nutrients that algae use derived from chicken poo?

Answer: Nitrates and phosphates.

91: What is nominative determinism?

Answer: Nominative determinism refers to where the name of someone determines their role in life (e.g. Hugh G. Wrection might be a scaffolder, specializing in large buildings).

92: Who wrote A Field Atlas of the Seashore?

Answer: Julian Cremona, the third warden of Dale Fort.

93: What is a fruiticose lichen?

Answer: A lichen that sticks up from the surface like a tiny shrub.

94: How many tanks (+ or – 10) does the British Army have ready for action?

Answer: 64.

95: What is the Ritec Fault?

Answer: The Ritec Fault is the reason Milford Haven exists. Two massive lumps of the earth’s crust collided and lots of rock was shattered. Shattered rock is easily eroded. This erosion is what created the valley of the River Cleddau. The fault extends right across South Pembrokeshire to Saundersfoot. It then extends right under Carmarthen Bay to The Gower.

96: When did Archbishop James Ussher claim that the world began?

Answer: In 1650, Archbishop Ussher used the dates and chronologies in the bible to enable him to announce that the earth was created at midday on October 23rd 4004 BC

97: When was the paddle steamer Albion wrecked?

Answer: 18th April 1837.

98: Where did Saint Brynach commune with angels?

Answer: On Carn Ingli, which means hill of angels.

99: How do you ensure instant eternal bliss upon shrugging off the mortal coil?

Answer: Simple, all you have to do is die immediately after being granted a plenary indulgence before you’ve had time to commit any more sins. There’s a fuller explanation of this in Blog Number 99.

There we are, the answers to all 99 questions and definitely the last time we’ll have a quiz this big written by me.

The response to the quiz was overwhelming but one entrant beat everybody else by several country parsecs.

The winner is:

Simon Wood of Cardiff and Marloes

Many congratulations to him and thanks from me for actually answering every question.

Simon, sporting curiously contrasting headgear, receives his prize at a glittering occasion on my laptop.

Second place went to Dr. Jonathan Hales of Chepstow.

Third place went to Nunzilla of China.

In fourth place was Arnold Swarzneggar of California.

Fifth was Sandy Morrell of Tish,

Sixth place was taken by Cornelius Probe of Allreggub, Carmarthenshire.

Look out for Blog 102,

I can confidently predict that it will not be a quiz…